Thursday, April 28, 2011

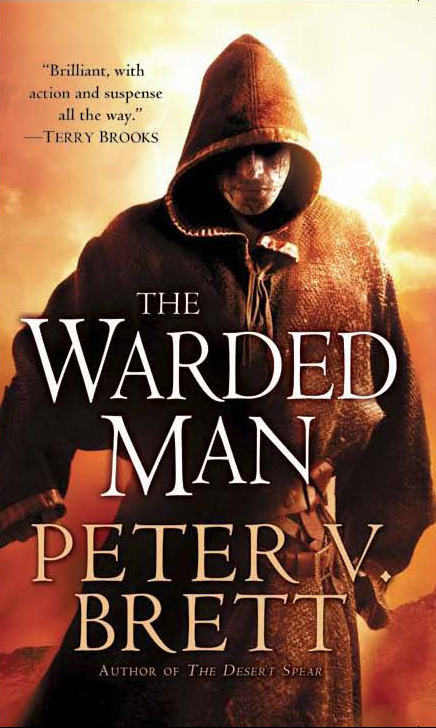

The Warded Man

[Note: I listed to this as an audiobook.]

The Warded Man is Peter V. Brett's 2007 debut fantasy novel. I sought it out after hearing it described online as a fresh, modern take on a genre that sees more rehashing than just about any other I can think of. While Brett's creation has some interesting diversions, overall the writing is unfulfilling and uses a number of the same, tired fantasy elements that are seen again and again in fantasy literature.

The novel is set in a world ravaged by demons. Each night, the corelings (as they are known), rise from the ground and proceed to wreak havoc on anything they can get their claws on. After a night of rampaging, they dissolve away in the light of the morning. The corelings are virtually indestructible, and even the most skilled human warrior would be powerless against them. Luckily for the humans, a series of wards that are drawn or etched provide a magical net capable of repelling the corelings. The demon scourge has completely shaped day-to-day life--travel is limited to the daytime, outlying communities are fairly small and isolated, a network of skilled messengers that courier messages and goods between communities has developed, warding is a highly sought after skill, etc. The worldbuilding in The Warded Man is fairly well realized and definitely the novel's strong point.

As the novel opens, wards are limited to a defensive role, though there are tales of wards long-forgotten that could give humans the power to fight to the demons. Wait, let me guess...you can see where this is going, right?

In steps Arlen, a...wait for it...ordinary boy from a poor village that has just been ravaged by a demon attack. After watching his mother die and the cowardice of his father in preventing that death, Arlen vows that his days of cowering in fear of the demons are over. He sets out to begin training as a messenger in the hopes of honing his martial skills to the point where he can begin to realize his dream of taking the fight to the corelings. In addition to Arlen, there are two other POV characters, Leesha and Rojer (oh how I hate that name), both also children raised from humble beginnings in outlying villages. As the novel progresses, the years slip by and the characters grow into adults and assume their roles in the society at large.

Now I won't spoil the big surprise about who the Warded Man turns out to be, but eventually the three characters meet up and are thrust into a desperate fight against a horde of demons bent on destroying Leesha's home village.

Now for the criticism...

1) It turns out that the plot was working up to...nothing! I kept waiting for some overarching storyline to assert itself, but other than a vague prophecy about a Deliverer coming to save the humans, there was nothing. The entire novel works up to a final battle scene with little or no consequence for anyone other than Leesha.

2) We learn absolutely nothing about the corelings other than what they look like and a bit about their animal-like behavior. Given that they relatively recently returned to the world after being banished for thousands of years, I would expect there is some story to tell there. To be fair, the novel is clearly written as the first of a series, so perhaps criticism 1 and 2 will be addressed in later volumes.

3) There were some really awkward sexual scenes in the novel that did little or nothing to advance the plot or characterization. I couldn't help but wonder if, by including these scenes, Brett was trying to make some sort of statement about morality. It was very reminiscent of Terry Goodkind's proselytizing in the Sword of Truth novels, and, quite frankly, off putting.

To sum up, The Warded Man was a moderately enjoyable novel with a serviceable, if derivative, plot. However, in the end, the criticisms I've noted above cheapened the reading experience quite a bit. I'll probably skip the sequel.

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Antony and Cleopatra

Antony and Cleopatra is Colleen McCullough's 2007 novel that wraps up her epic (and I do mean epic) 'Masters of Rome' series. While it is good to bring a sense of closure to the series, I think that this novel lacked some of the spark of the previous volumes. Perhaps McCullough lost a bit of her muse with the death of Julius Caesar in the last volume, The October Horse (though his specter hangs over the entire novel).

[To be fair, it should be noted that McCullough considers the Roman Republic to have ended with the defeat of Caesar's assassins in 42 BC and originally intended to conclude her series with The October Horse. She buckled to pressure and wrote Antony and Cleopatra to appease her legions (pun definitely intended) of fans.]

The novel opens in 41 BC in the aftermath of the Battle of Phillipi. Two years before, the Roman world has been divided into two parts (well, to be technical, there are three, but who counts the oft-overlooked Lepidus anyway?): the west, controlled by Octavian, and the east, by Mark Antony. The delicate balance of power that has kept the two from each other's throats since the death of Julius Caesar is slowly unraveling.

Octavian struggles to consolidate his power in Italia in the face of growing discontent over the price of wheat, inflated by the constant raiding of that piratical nuisance, Sextus Pompey. In the east, Mark Antony is intent on leading a campaign against the Parthian empire which he hopes will bring him untold wealth along with the prestige he needs to stand above Octavian once and for all. Into the mix comes Cleopatra, pharaoh of Egypt and once lover of Julius Caesar, who has her own designs on power in the Mediterranean region. She recognizes in Mark Antony a tool she can use to promote her own interests (i.e. making her son by Julius Caesar king of Rome) and sets out to ensnare him with first wealth and, later, her feminine wiles.

Antony and Cleopatra is a solid conclusion to the Masters of Rome series--without a doubt it upholds the high standard I've come to expect from McCullough. The history is well researched. The characters jump off the page. At the same time, it lacked the spark of the previous volumes until the very climax of the story (hence the somewhat lower hamster rating).

So there you have it: after seven books comprising several thousand pages, the events of 110-27 BC come to a conclusion! Big thanks (and much respect) to Mrs. McCullough for making the events and people of the twilight of the Roman Republic come to life. Her 'Masters of Rome' series is truly a masterful achievement that I would recommend without hesitation (at least to those with some measure of literary stamina) .

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

The Defection of A.J. Lewinter

A friend recommended The Defection of A.J. Lewinter (1973) by Robert Littell during a recent tour of his bookshelf. Having just finished an epic game of Twilight Struggle, the novel piqued my interest. It turned out to be a smart, tightly written novel with a lot to say about the nonsensical nature of espionage.

The novel opens up with the attempted defection of A.J. Lewinter, an academic and specialist in the field of missile ceramics, to the Soviet Union. While at a scientific conference in Tokyo, he walks into the Soviet embassy offering to share information related to the trajectory of warheads used in the MIRV missile system of the United States. This is, of course, highly valuable information to the Soviets, as it could facilitate the development of a more capable Soviet missile defense system.

After this opening salvo, the novels alternates between the viewpoints of American and Soviet intelligence agents. The Americans have to try and determine what, if any, security risk Lewinter's defection poses. Did he actually have access to any sensitive information? What were his motives? It is likewise up to the Soviets to determine what exactly to do with Lewinter and his information. Should they act on his information? Is he best used as political propaganda? Most importantly, could he be an American plant? Littell does a good job of doling out enough information about Lewinter that any scenario proposed by either side seems plausible.

I didn't expect anything more than a good spy story when I first began the novel. However, it quickly becomes clear that Littell is smartly commenting on the absurdity of intelligence operations. Consider the following snippet from a conversation between two of Lewinter's Soviet handlers:

"...it is also possible the Americans were trying to make it appear as if they were reacting to a genuine defection in order to convince us that Lewinter had valuable information. In which case, he would be a fraud. Or the Americans may have been trying to convince us he's real knowing we'd discover they were trying to convince us he's real and conclude instead he's a fraud. Which would mean they want us to think he's a fraud. Which would mean he's genuine."The novel is full of little bits that call into question the sanity of high-stakes espionage between the United States and Soviet Union.

The Defection of A.J. Lewinter has little in the way of overt action. Espionage is portrayed as a highly cerebral psychological game (comparisons to chess are rampant) played by men in small rooms that are worlds apart from each other. It is undoubtedly a more realistic portrayal of espionage than anything offered by the likes of James Bond or Jason Bourne.

I thoroughly enjoyed the novel, and I look forward to following it up soon with 'The Company,' Littell's definitive work about the American intelligence community.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)