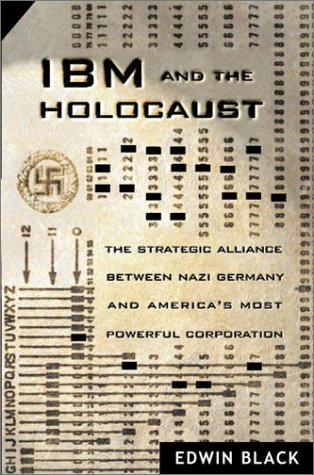

Edwin Black does a magnificent job detailing the role that the technology controlled by International Business Machines played in accelerating the pace of the Holocaust. In the introduction to the book, Black unequivocally states so as the reader does not make a mistake: the Holocaust would have still happened without IBM's involvement. However, without the automation supplied by IBM, the process would have been vastly less efficient. Case in point: the stark contrast between the high percentage of Jews eliminated in Holland (which had an established IBM presence and expertise in automated census counting) and the much lower rate in France (where the market for automated census equipment was fragmented and not well developed).

One gripe: I would have liked the account to have had a more technical discussion of how Hollerith machines used. I understand on a basic level how alphabetizing and sequential sorting based on categories could be applied to counting people. However, how these operations might be applied to something as complicated as cargo scheduling and maintaining a train transportation network were not clear to me.

Reading the book has given me a new perspective on the power of a census. The information (in many cases) voluntarily given to the Nazis by many Jews spelled their own doom throughout the Reich. The next time I'm filling out a form asking for seemingly unimportant personal details I might give pause to consider how the information might be used.

I went into this book not knowing how I would react. Isn't the job of a multinational corporation such as IBM to make money? I would suggest that the answer is "yes" but there is a moral line that should not be crossed to do so. Black's account proves that IBM didn't just step over the line but kept on walking and didn't look back. One example: IBM sent technicians into concentration camps to service the Hollerith machines that were clacking away sorting Jews to the gas chamber. It is a story of greed gone unchecked--there is no doubt in my mind that IBM, and particularly Thomas J. Watson, has blood on their hands.